Cancer research has long relied on the use of in vitro cell lines as pivotal models to understand the mechanisms of the disease and evaluate potential treatments. These cell lines allow researchers to simulate biological processes in a controlled environment, enabling reproducibility and scalability. However, a major limitation of many studies is the lack of comprehensive demographic and genetic characterization of the cell lines used. Specifically, the underrepresentation or incomplete identification of ancestry information poses challenges to the generalizability and precision of research outcomes. Understanding the ancestry of cell lines is critical as it provides context for genetic variations, disease susceptibility, and drug response patterns among diverse populations. Addressing this gap is essential for achieving equitable and effective cancer therapies.

Ancestry distribution among cancer cell lines

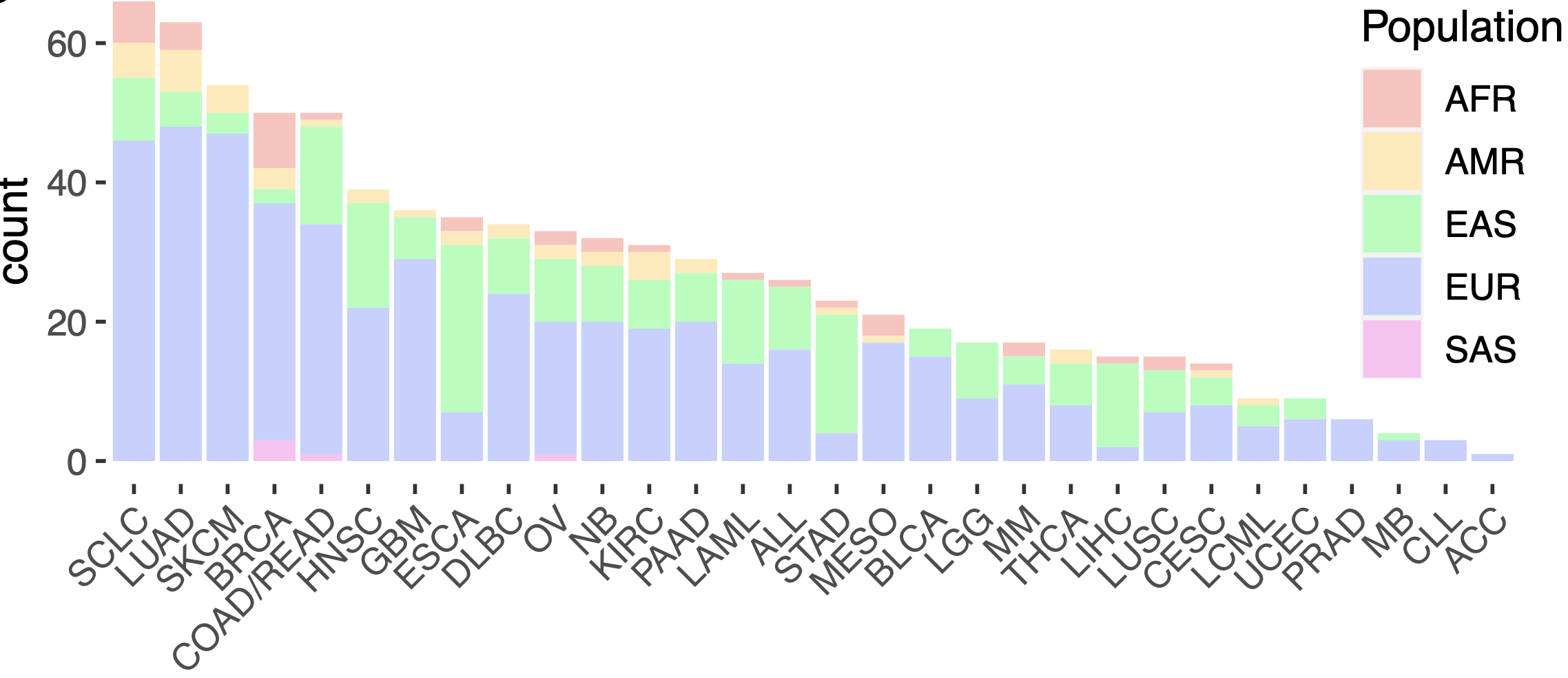

To tackle this issue, I developed an ancestry inference pipeline designed to accurately classify the genetic backgrounds of a wide range of cancer cell lines. Leveraging extensive genetic data of the cell lines, the available reference genomes for all ancestries and Bayesian statistics, the pipeline infer ancestry with high precision. Details of the pipeline could be found in a separate post. To this end I leveraged the cell lines and their genotype data obtained from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) project and the reference genomes from the five major ancestries from the 1000 Genomes Project. The analysis revealed a detailed distribution of ancestries across commonly used cancer cell lines, highlighting a predominance of European-derived lines alongside underrepresentation of African, Asian, and other ancestries (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of ancestries in cancer cell lines across cancer types. European cell lines are predominantly represented in all cancer types.

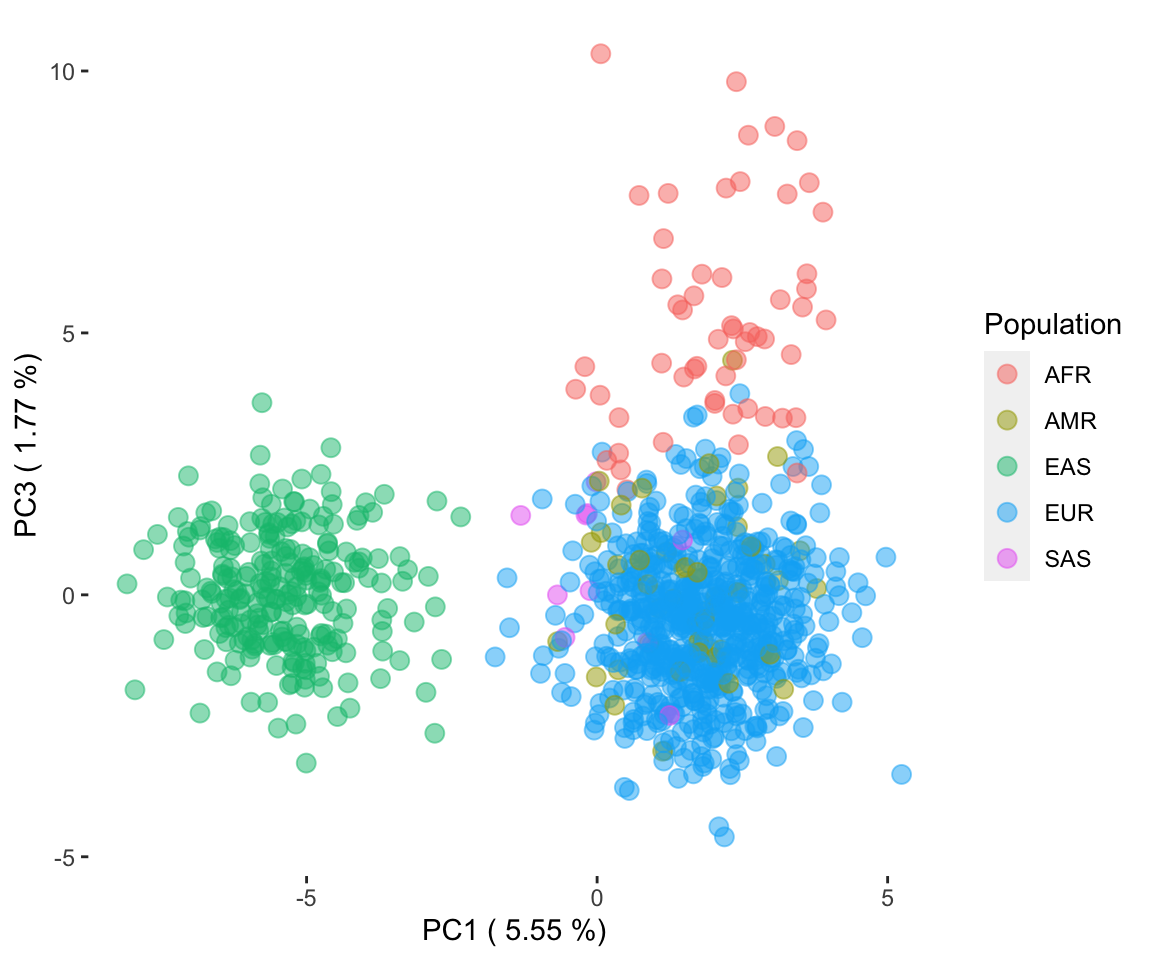

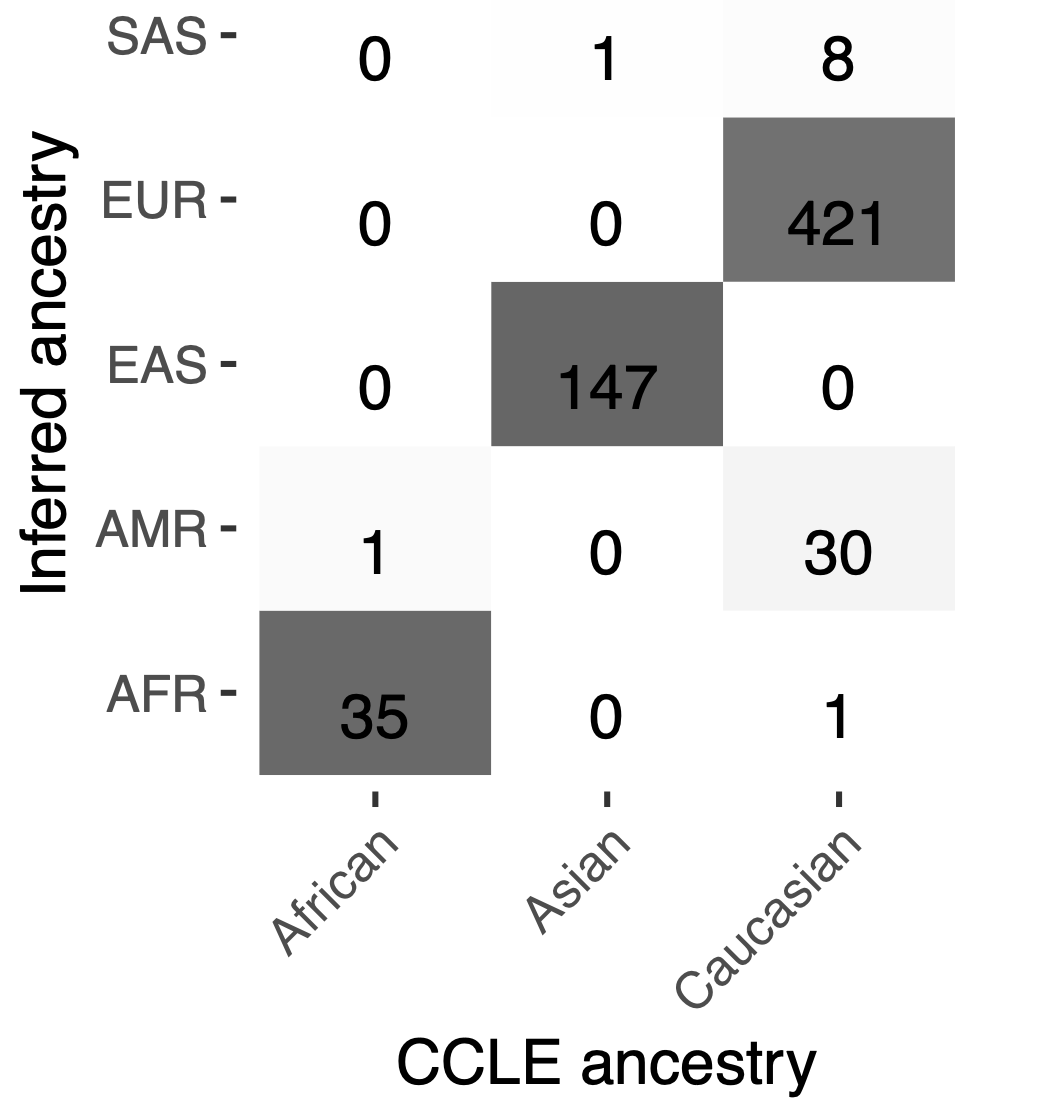

The ancestries identified segregated tightly together and away from other ancestries when visualized using PCA on genetic data (Figure 2). Importantly, the inferred ancestry classifications were cross-validated against known demographic information in the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia project (CCLE), demonstrating strong consistency and reliability of the methodology (Figure 3). These findings underscore the utility of the pipeline in providing a clearer demographic landscape of cancer cell lines and emphasize the necessity of incorporating diverse genetic backgrounds in cancer research.

Figure 2. PCA of the three major ancestries of cancer cell lines.

Figure 3. Cell lines were accurately classified into ancestries using our pipeline, when compared against CCLE information

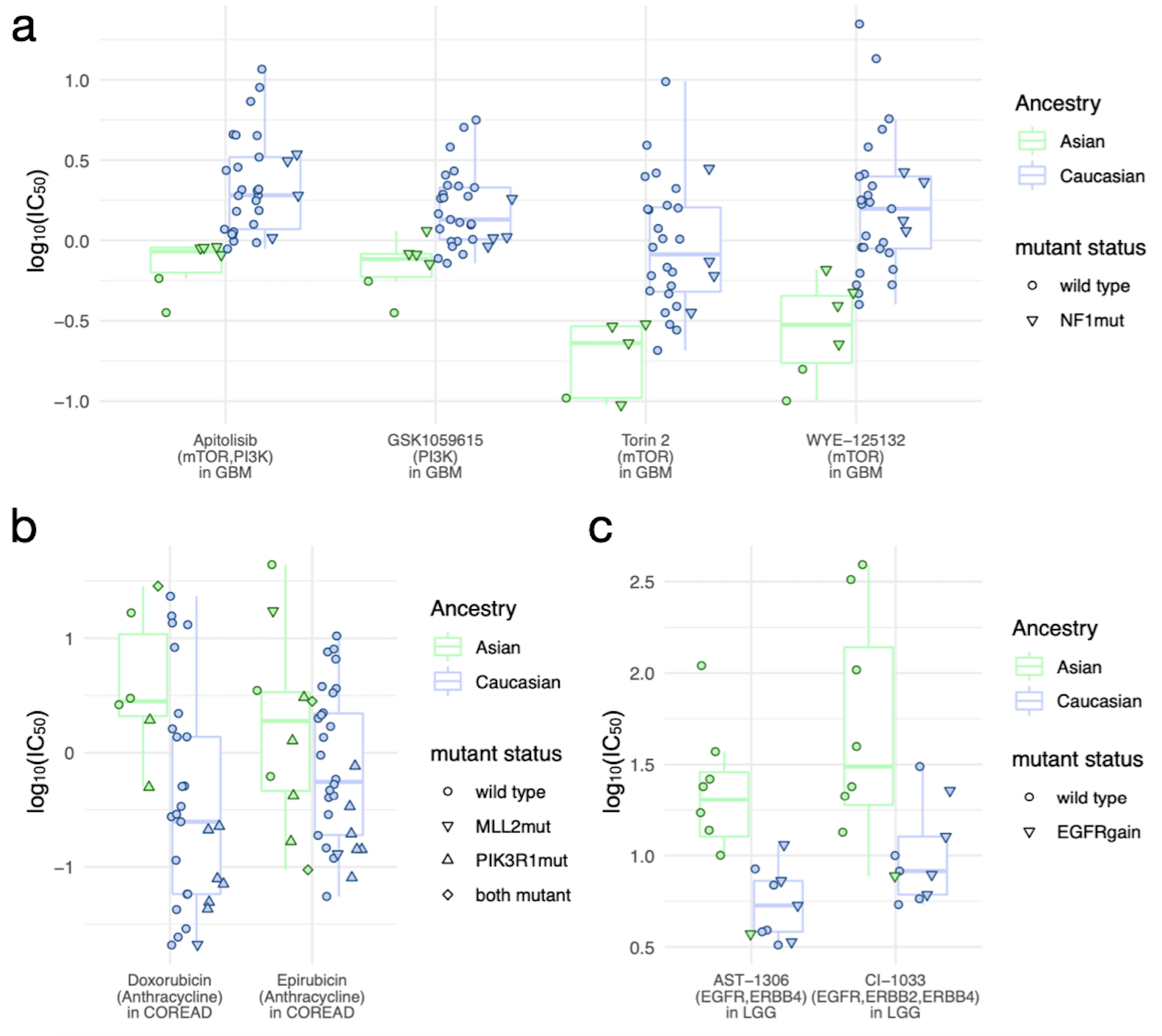

Disparities in drug response between Asian and Caucasian cell lines

An intriguing aspect of the study is its exploration of disparities in drug responses between Asian and Caucasian cell lines. One-way ANOVA tests revealed 59 significant associations between ancestry and drug response across nine cancer types. Asian cell lines demonstrated heightened sensitivity to PI3K/mTOR inhibitors in glioblastoma (GBM), particularly drugs like apitolisib (Cohen’s d = −1.73), torin 2 (Cohen’s d = −1.87), and WYE-125132 (Cohen’s d = −1.91) (Figure 4a). These findings were linked to enriched targets, such as PI3K and mTOR pathways, in Asian GBM cell lines. Conversely, Caucasian cell lines showed greater sensitivity in colorectal adenocarcinoma (COREAD), with all 16 significant associations favoring drugs like anthracyclines (e.g., doxorubicin and epirubicin) (Figure 4b). Additionally, Caucasian-derived low-grade glioma (LGG) cell lines exhibited higher sensitivity to irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as AST-1306 and CI-1033, targeting EGFR pathways (Figure 4c). While somatic mutations, such as NF1 in Asian GBM and MLL2 or PIK3R1 in COREAD, were more prevalent in specific ancestries, they did not fully account for the observed variability in drug responses. These results highlight the critical role of ancestry-informed biomarkers in guiding cancer therapies and suggest opportunities to tailor treatments for improved outcomes in diverse populations.

Figure 4. Significant associations between drug response and ancestries (Asian and Caucasian)

Discussion

The novel findings of this study lie in its development of a robust ancestry inference pipeline, which accurately classifies the genetic backgrounds of cancer cell lines. This analysis revealed a predominantly European ancestry distribution, underscoring the need for broader representation of non-European genetic backgrounds in cancer research. These findings have significant implications for the development of more inclusive cancer therapies and equitable healthcare solutions.

That being said, the study is not without limitations. The limited genetic information available for certain cell lines poses challenges in fully validating ancestry-specific biomarkers and their clinical relevance. Although there are many available genomic imputation techniques, the reliability of these methods is still under evaluation. Furthermore, inherent differences between in vitro cell line models and in vivo human cancer processes may limit the applicability of the findings to clinical settings. Experimental validation and observational data should be leveraged to validate the findings. The authors highlight the necessity of incorporating more diverse genomic data and refining methodologies to bridge these gaps, ensuring that future research captures the complexity and heterogeneity of cancer across all populations.

For an in-depth discussion of this study please visit the original publication. Code for the analysis and computational pipeline could be found on my github repository.